The North American economy is not in recession but the risks are elevated given restrictive monetary policy geared at slowing economic growth, says a new report by TD Economics.

“Rising unemployment is the most salient feature of recessions. Historically, the U.S. unemployment rate has shown more sensitivity to economic deterioration than the Canadian unemployment rate,” it said.

“During recessions high-productivity sectors in Canada often see larger declines than their U.S. counterparts. Meanwhile, U.S. recessions have been more widespread, resulting in larger overall job losses. Despite larger labour markets shocks, recoveries from recession have been faster in the United States and unemployment rates have returned more quickly to pre-recession levels than in Canada. Higher Canadian labour force growth may be a game changer since it requires a higher employment bar to stabilize the unemployment rate.”

Here’s the full report:

Recession fears have been looming since last year as tighter monetary policy amplify the odds of the economy losing its footing. Recessions are defined by significant and widespread declines in economic activity that last longer than a few months.1 A rising unemployment rate is the most salient feature of recessions.2 Should the North American economy stumble into recession, the rate of joblessness will be of paramount concern.

Recession fears have been looming since last year as tighter monetary policy amplify the odds of the economy losing its footing. Recessions are defined by significant and widespread declines in economic activity that last longer than a few months.1 A rising unemployment rate is the most salient feature of recessions.2 Should the North American economy stumble into recession, the rate of joblessness will be of paramount concern.

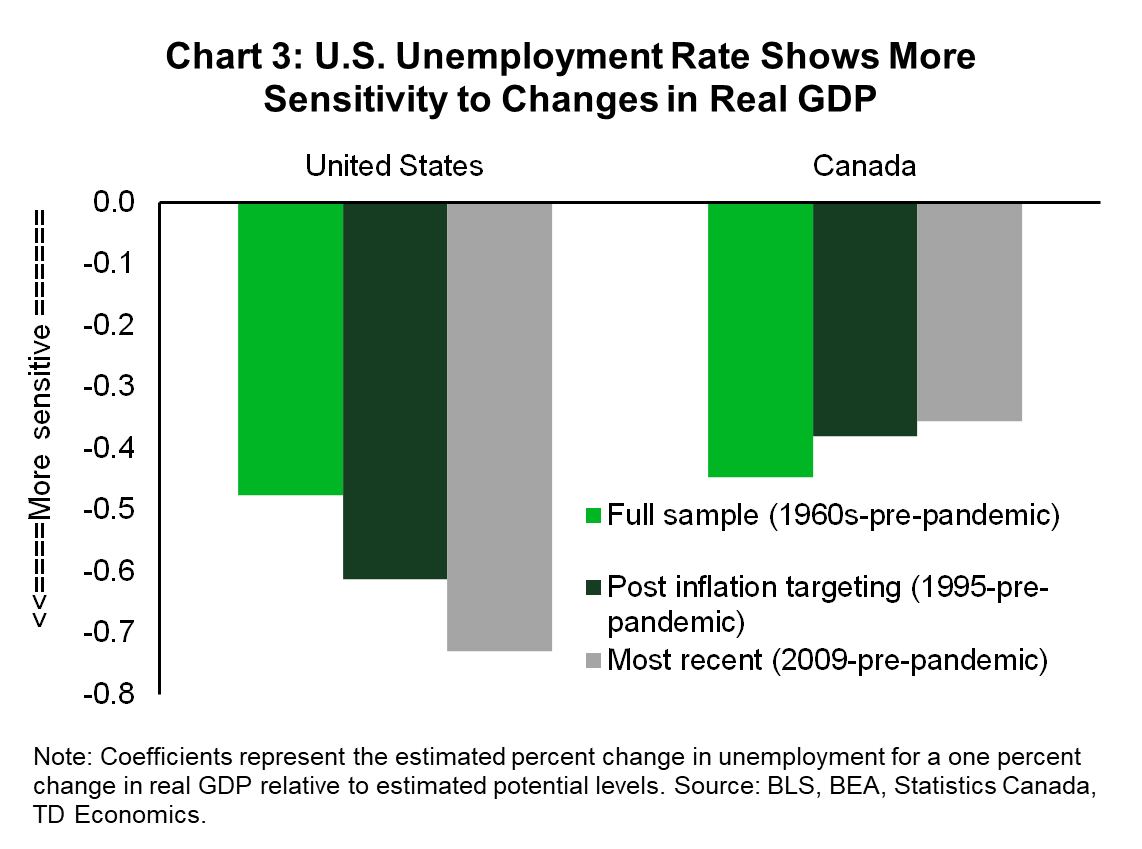

Historically, the U.S. unemployment rate has been more sensitive to changes in real GDP growth than Canada’s. We estimate that for every percentage point increase in the gap between actual and potential real GDP, the unemployment rate is likely to rise 0.5 percentage points, compared to 0.4 percentage points in Canada. This cross-border gap has widened since the Global Financial Crisis. A relatively larger decline in GDP within high-productivity sectors during recessions helps explain why Canada often walks away with fewer labour market casualties.

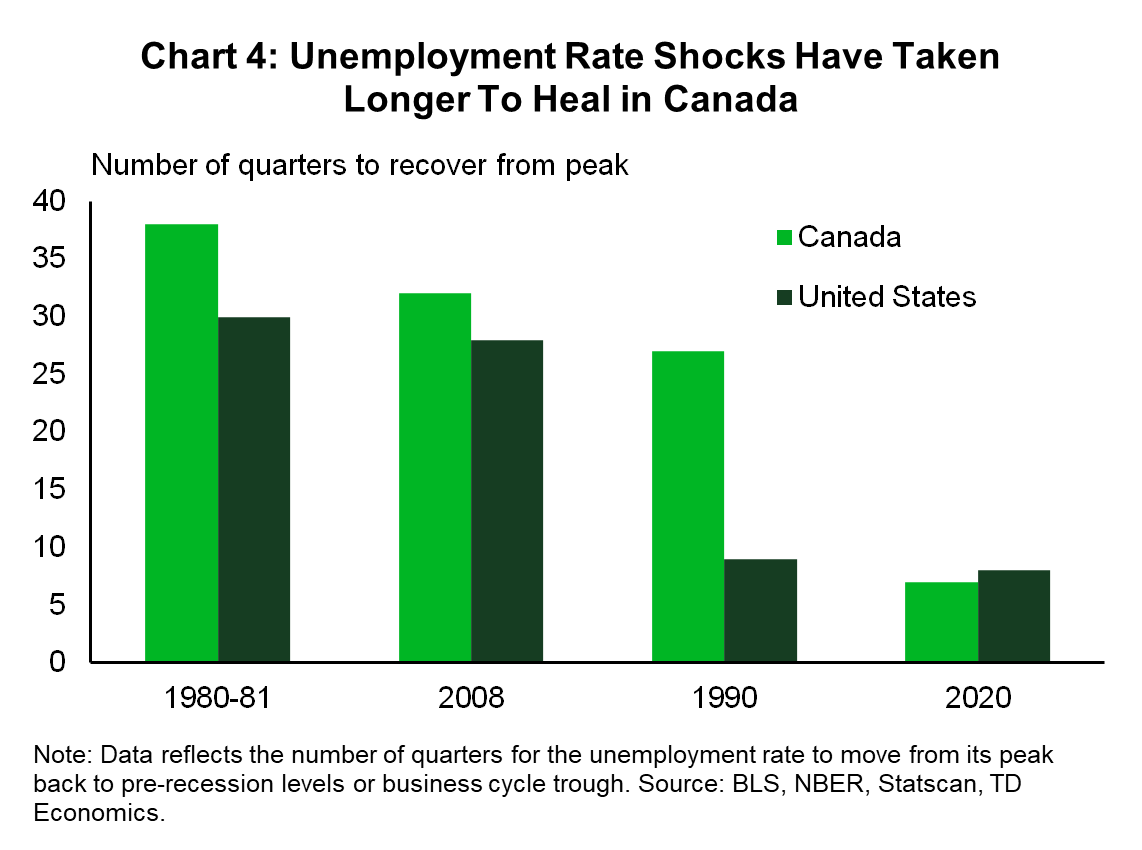

The U.S. has historically seen larger increases in unemployment than Canada, but its unemployment rate recovers faster than Canada’s – typically reaching its pre-recession level a year earlier.3 Differences in industrial composition, labour laws, and unionization rates likely explain this phenomenon.

While historically Canada’s unemployment rate has been less sensitive to changes in GDP, the current rapid pace of labour force growth may be a game changer. With a much faster labour force growth in Canada relative to the U.S., a higher job creation bar will be needed to avoid increases in unemployment. Canada may not experience the same breadth of job losses as the U.S. but could still face increases in unemployment. (For more on our outlook for the Canadian labour market please see our recent report).

Recessions Have Been Harder on Canada’s Economy, Gentler on its Labour Market

Since the 1970s there have been six recessions that have hit both the United States and Canada.4 The economic gravity of these downturns can be captured in the depth of declines in real GDP (peak-to-trough) and increases in unemployment rates (Table 1). Canada has seen larger declines in real GDP than the United States over these six episodes. In fact, for every recession experienced in both countries since 1981, declines in real GDP have been greater in Canada than in the United States.

Downturns hit GDP harder north of the border but increases in the unemployment rate have been more pronounced in the United States. The two exceptions are the deep recessions of the early 1980s and early 1990s, when both Canadian real GDP and the unemployment rate underperformed the U.S.

The pattern of relatively smaller increases in unemployment during recessions is most evident during the two most recent episodes – the GFC and the pandemic downturn. In both these cases Canada’s real GDP saw bigger declines, but the rise in its unemployment rate was more muted than in the United States.

Table 1: Real GDP and Unemployment Rate During Recessions

| Real GDP Peak-to-Trough (% Change) | Unemployment Rate Trough-to-Peak (Pctg. Pt. Chg.) | |||

| Year | Canada | U.S. | Canada | U.S. |

| 1974 | -1.1 | -3.1 | 3.3 | 4.1 |

| 1980 | -0.1 | -2.2 | 0.5 | 1.4 |

| 1981 | -5.4 | -2.6 | 5.8 | 3.3 |

| 1990 | -3.4 | -1.4 | 4.1 | 1.9 |

| 2008 | -4.4 | -4 | 2.5 | 5.1 |

| 2020 | -12.8 | -9.6 | 7.7 | 9.4 |

| Mean | -4.5 | -3.8 | 4 | 4.2 |

| Median | -3.9 | -2.9 | 3.7 | 3.7 |

U.S Downturns Have Tended to Fuel More Widespread Increases in Joblessness

The pattern of larger declines in real GDP in Canada during recessions is consistent with an economy that has, on average, underperformed the U.S. in terms of real GDP and growth. However, this pattern also appears to be compounded during recessions.

The pattern of larger declines in real GDP in Canada during recessions is consistent with an economy that has, on average, underperformed the U.S. in terms of real GDP and growth. However, this pattern also appears to be compounded during recessions.

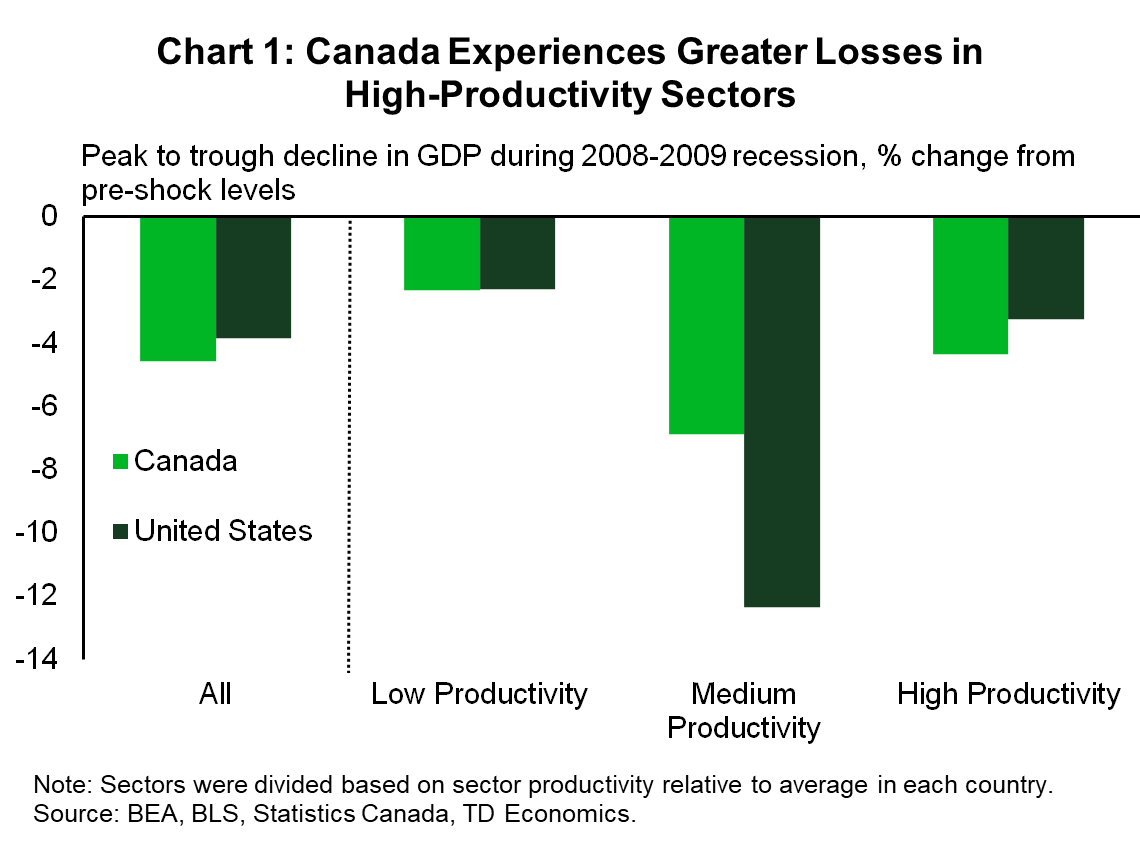

To understand why it’s necessary to look under the hood at changes in real GDP across industries. By comparing labour productivity (measured by real GDP per hour worked) across industries, we see that relatively more productive industries have suffered greater declines in GDP during recessions in Canada relative to the U.S. During the GFC, industries with productivity levels 50% above the national average suffered total declines of 4.3% in Canada versus 3.2% in the U.S. At the same time industries with productivity levels hovering around the national average experienced much bigger declines in the U.S. relative to Canada (12.3% vs 6.9%). Greater GDP declines in relatively high productivity sectors helps to explain the smaller unemployment rate changes in Canada during recessions. It also helps to explain Canada’s worsening productivity performance vis-à-vis the U.S., which has seen bigger jumps during and following economic downturns.

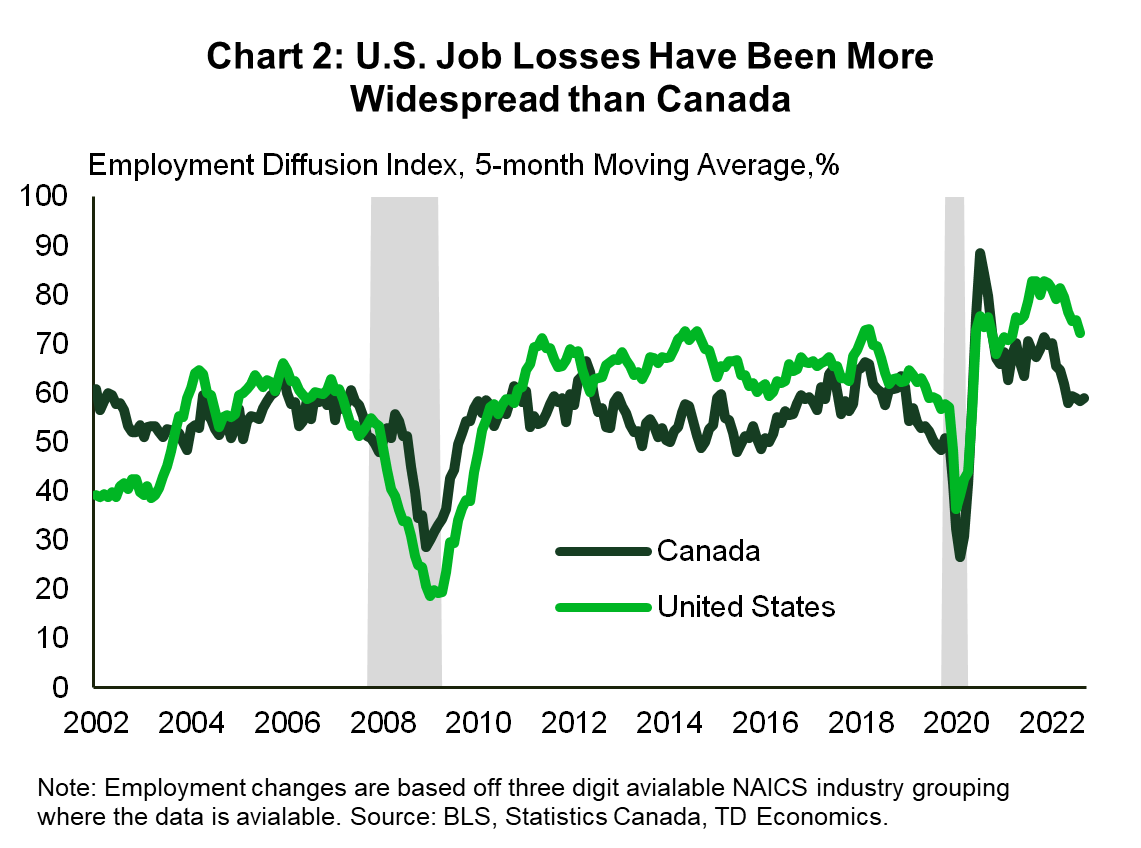

Another differentiating feature of business cycles between the two countries is that U.S. downturns have tended to result in a greater breadth of job losses across industries relative to Canada.5 Employment diffusion indexes that capture the breadth of industries suffering job losses show that U.S. declines have – with the brief exception of the pandemic lockdown period – tended to be more widespread, while Canada’s more concentrated (Chart 2).6,7

Quantitative Models Tell the Same Story

The relationship between changes in unemployment and production (measured by real GDP) is known as Okun’s law (or Okun’s rule after the economist Arthur Okun). There are various ways to estimate it. The most straightforward way is to simply regress changes in real GDP on changes in unemployment rate and examine the size of the coefficients. Doing so shows a bigger response to changes in GDP on unemployment in the U.S. than in Canada.

The relationship between changes in unemployment and production (measured by real GDP) is known as Okun’s law (or Okun’s rule after the economist Arthur Okun). There are various ways to estimate it. The most straightforward way is to simply regress changes in real GDP on changes in unemployment rate and examine the size of the coefficients. Doing so shows a bigger response to changes in GDP on unemployment in the U.S. than in Canada.

A more sophisticated approach controls for structural changes in GDP and unemployment rates over time, measuring the impact of deviations in real GDP and unemployment from their estimated potential levels. This “output gap” approach yields similar results. The U.S. unemployment rate is more responsive to changes in real GDP than is Canada’s, with coefficients of -0.5 and -0.4 percentage points respectively (Chart 3).8

Previous empirical studies that looked at cross border elasticities of this relationship confirm this finding, reporting relatively stronger impulses from GDP changes to unemployment in the United States than in Canada.9 Looking at the evolution of this relationship over time, our results hold across different time periods. In fact, this cross-border gap appears to have widened since the onset of the global financial crisis.

U.S. Unemployment Rate Rises More, but Also Recovers Faster

One measure of the flexibility of a labour market is how quickly it responds to economic shocks both on the way down and on the way back up. By this metric, the U.S. is the clear winner. While the U.S. tends to shed jobs faster than Canada, it also recovers them more quickly. As a result, during economic recoveries, the U.S. unemployment rate has tended to move back to pre-shock levels sooner. Looking across recessions, the median timeframe to return to pre-pandemic unemployment rate levels is roughly one year faster in the U.S. (Chart 4). 10

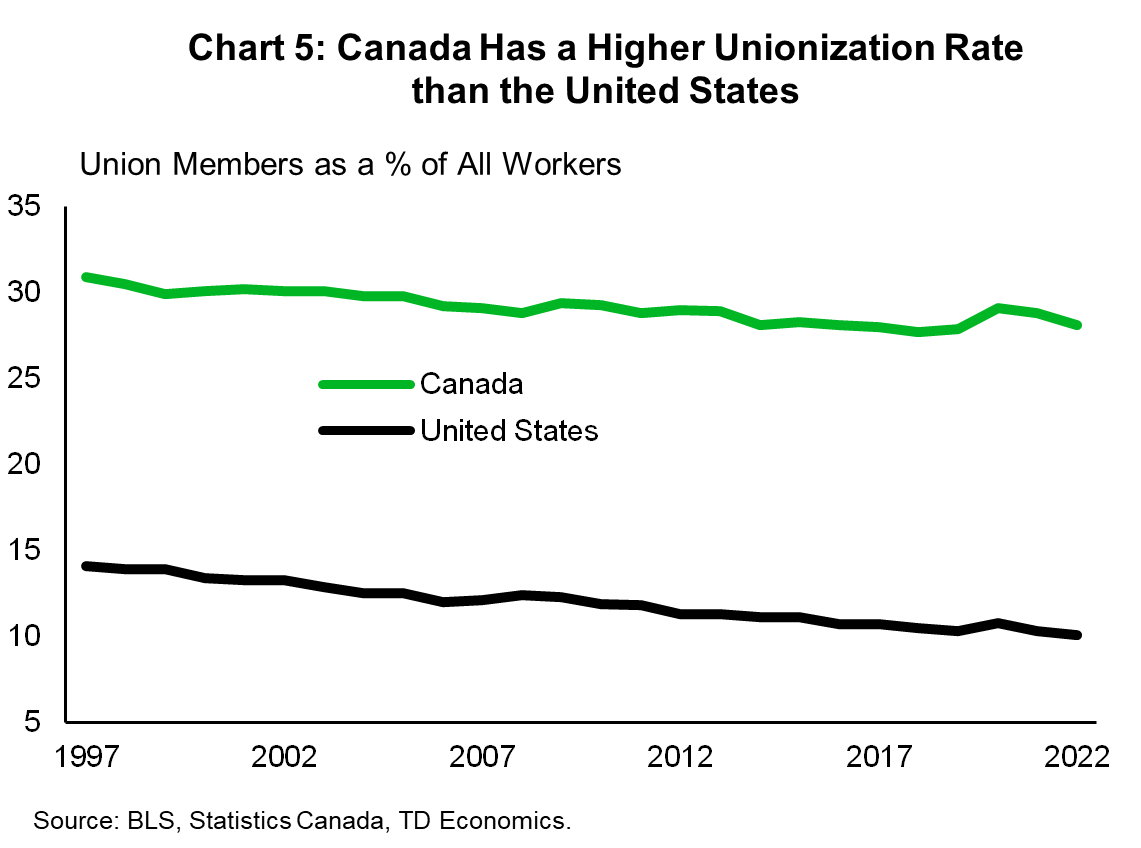

Structural differences in labour laws between Canada and the U.S. likely explain its relatively greater flexibility. Canadian employment laws have more conservative covenant terms governing things like termination, severance policies and employment litigation.11 At the same time, higher rates of unionization in Canada make layoffs more difficult but may also make rehiring more challenging (Chart 5).

Faster Labour Force Growth May Change the Dynamic This Time Around

While the U.S. unemployment rate is more sensitive to changes in real GDP, the notable acceleration in Canadian labour force growth (in contrast to the U.S.), suggests that Canada’s unemployment rate may face a new headwind unrelated to past experience. Faster labour force growth means that jobs must rise at a faster rate just to keep unemployment rate steady. Should they fall below it, unemployment will rise.

At the same time, with higher levels of household debt potentially weighing more heavily on demand, Canada may see a greater economic underperformance than observed historically. Even with relatively less sensitivity to changes in GDP, there are notable downside risks to the Canadian labour market.

The Bottom Line

Recession fears often bring into focus the potential scars to the labour market. With a similar-sized economic shock, history would suggest that the United States is prone to a larger increase in its jobless rate. While the Canadian labour market may be more insulated against the adverse effects of an economic downturn, it is also likely to recover more slowly, prolonging the duration of joblessness.

The rapid acceleration in Canada’s population and labour force growth means unemployment could increase even with a relatively small economic shock. That raises the stakes, especially for workers who are newer to the labour force and those with smaller skills premiums.

Mario Toneguzzi

Mario Toneguzzi is Managing Editor of Canada’s Podcast. He has more than 40 years of experience as a daily newspaper writer, columnist, and editor. He was named in 2021 as one of the Top 10 Business Journalists in the World by PR News – the only Canadian to make the list)

About Us

Canada’s Podcast is the number one podcast in Canada for entrepreneurs and business owners. Established in 2016, the podcast network has interviewed over 600 Canadian entrepreneurs from coast-to-coast.

With hosts in each province, entrepreneurs have a local and national format to tell their stories, talk about their journey and provide inspiration for anyone starting their entrepreneurial journey and well- established founders.

The commitment to a grass roots approach has built a loyal audience on all our social channels and YouTube – 500,000+ lifetime YouTube views, 200,000 + audio downloads, 35,000 + average monthly social impressions, 10,000 + engaged social followers and 35,000 newsletter subscribers. Canada’s Podcast is proud to provide a local, national and international presence for Canadian entrepreneurs to build their brand and tell their story.